Santa Monica Basin | 33.7°N, 118.84°W | September 26, 2021

Well, this is different.

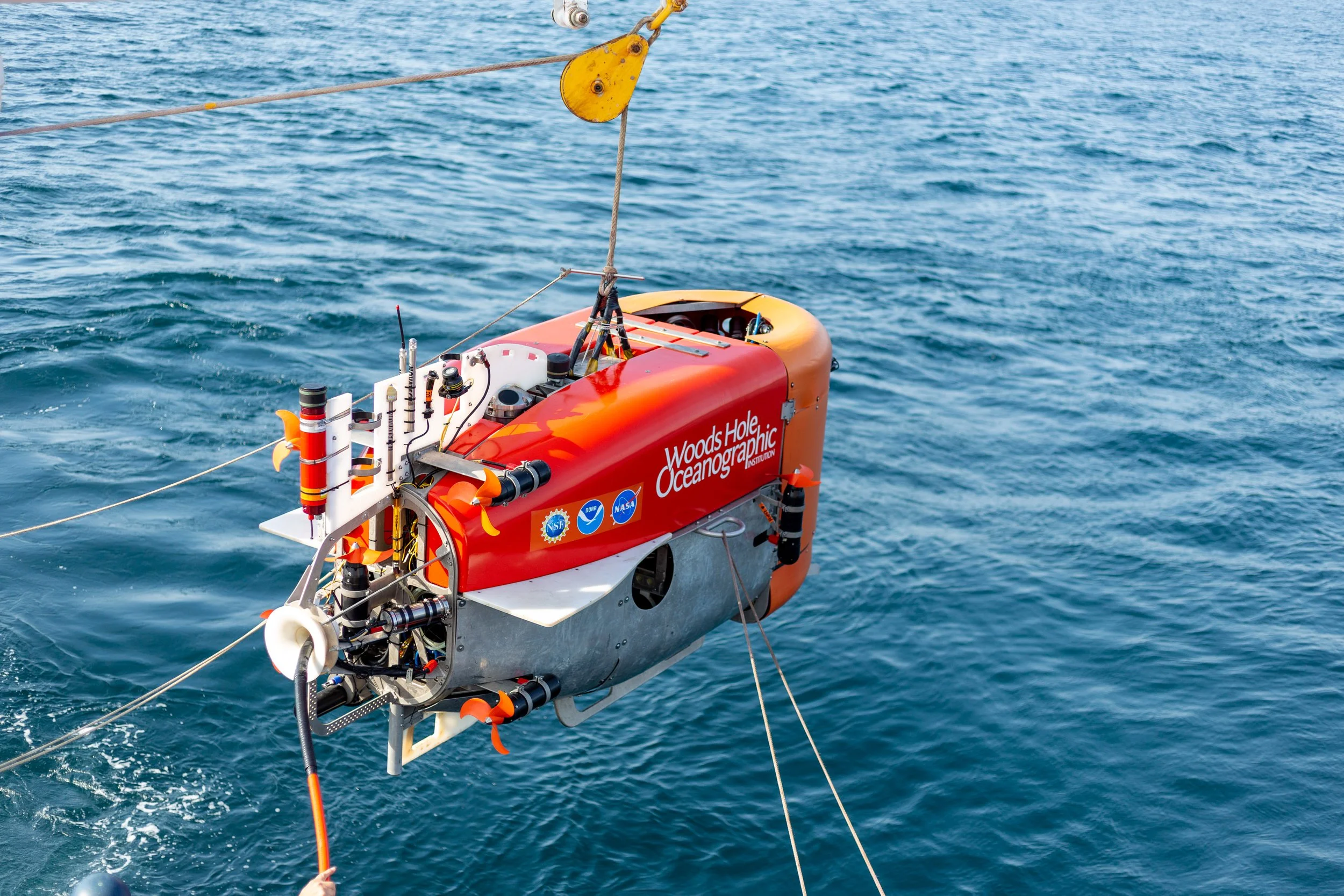

I have just boarded the E/V Nautilus in San Pedro, California. While I immediately recognize the friendly faces of my shipmates (even obscured behind masks), the aft deck contains several changes: a new extension, a new crane, and some distinctive ocean robots. In place of ROV Hercules, there is a bright red and orange vehicle called HROV Nereid Under Ice (NUI) and an eye-catching yellow robot called Mesobot, both from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI).

On this expedition, our team, including several scientists and engineers from WHOI, will demonstrate the capabilities of these ocean robots, both individually and in tandem.

Jason Fahy, our expedition leader, explains the importance of using multiple robots to expand exploration possibilities in the deep ocean.

“You have to remember these systems operate in harsh environments. And one system can’t do everything,” Jason says. “You have to have multiple nodes and teammates to make the chain work. We’re doing these building block demonstrations to see what works well together.”

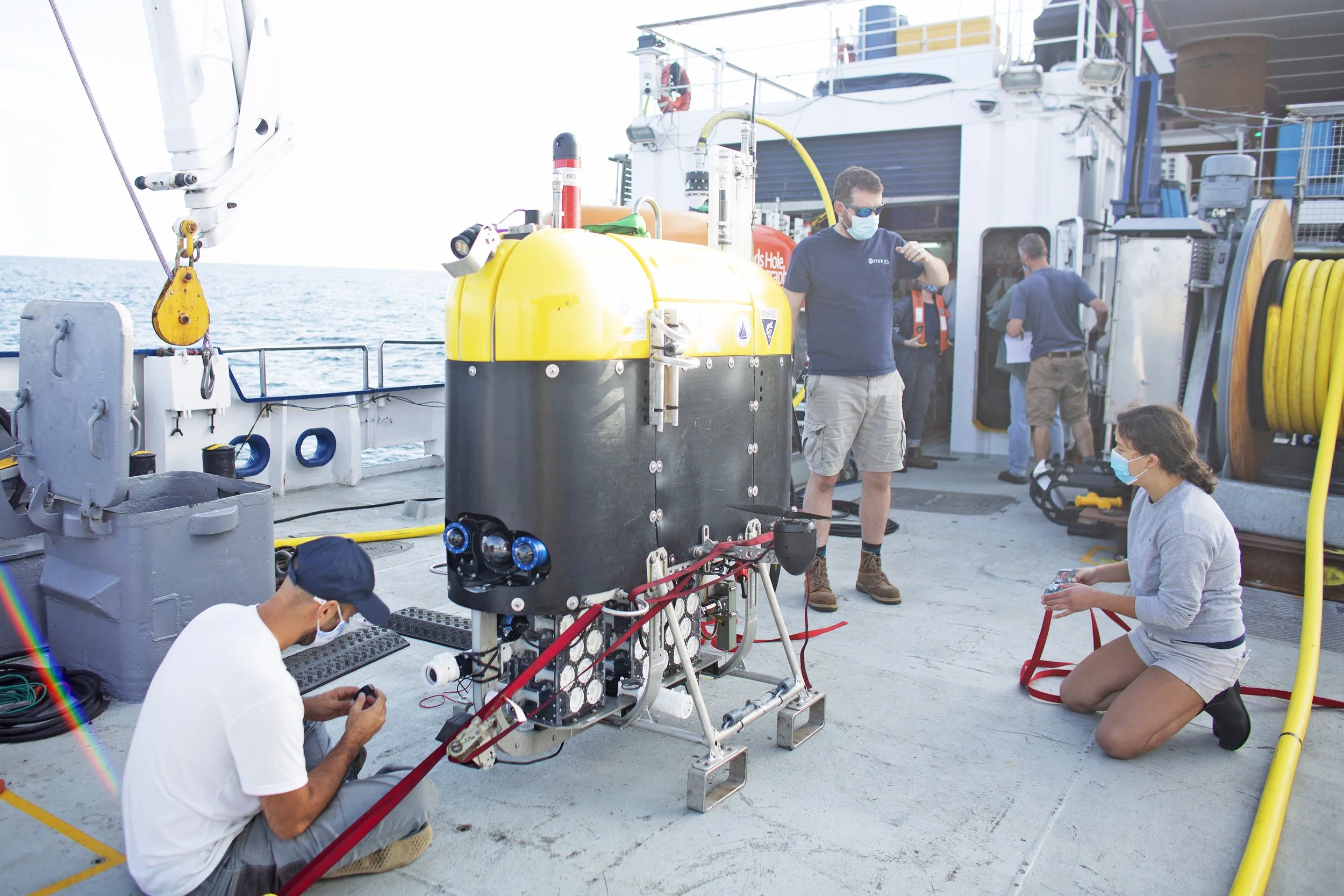

Lui Kawasumi runs through a checklist before a Mesobot dive.

NUI goes into the water using the same crane that deploys ROV Hercules.

The official description of our expedition goals states:

Funded by NOAA Ocean Exploration through the Ocean Exploration Cooperative Institute (OECI), one of the OECI’s goals is to build towards autonomous vehicles sharing information, allowing each vehicle to be more effective and to provide increased situational awareness to the vehicle operators aboard or ashore.

In other words, we’re going to try some things that haven’t been done before.

“For the OECI a ‘technology demonstration’ isn’t highlighting things that have already been achieved,” Jason says. “It’s the at-sea culmination of innovation in support of something previously thought impossible.”

During our first official day of operations, I’m sitting on the social deck, finishing a cup of coffee and editing photos. The door to my right opens and Bob Ballard rushes by. As he does, he turns to me and says, “get up to the control van! History is being made!”

Abandoning my coffee and laptop, I grab my camera and run up to the control van. As soon as I enter, I see over a dozen people crowded near the back row, watching with bated breath as Casey Machado operates NUI’s manipulator arm. Remote manipulation of a robotic arm is nothing new — the difference here is that NUI is free floating in the water with no tether or physical connection to the ship. An optical modem on ROV Argus acts as a “wireless hotspot” to pass video and control information from NUI back to the ship. While the video is pixelated and sometimes a bit glitchy, everyone in the room shares the excitement of seeing the future or ROV operations firsthand.

Casey Machado operates the manipulator arm of NUI via an optical modem for the first time.

Paul Glick oversees control of Argus during a NUI dive.

The spirit of advancing technology pervades both our work and casual conversations. During lunch one day, Paul Glick shares some history from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He explains that even at a place like JPL (where the official motto is “Dare Mighty Things”) people can be reticent to change.

“Back in the early days of Mars exploration, the engineers who designed and built the landers thought it was insane to include a rover,” he says. “They thought it would add too many extra variables that could mess up the payload.”

The Mars Pathfinder mission successfully delivered the first wheeled vehicle to the Red Planet on July, 4th 1997. The small rover, called Sojourner, was supposed to roam across the surface of the planet for just over a week. Instead it remained active for 85 days, blowing away all expectations and preconceived notions about the viability of its technology, and laying the foundation for the decades-long Mars rover program.

“Now that rovers are the norm,” Paul continues. “Some of the engineers who worked on Perseverance thought it was crazy to include a helicopter.”

Fortunately here on Nautilus, we don’t think trying out new technologies is crazy — we think it’s essential.

The Mesobot team prepares for another evening dive from the aft deck.

Erin Frates processes samples in the Wet Lab.

In the wet lab, I photograph Erin Frates as she processes samples from the most recent Mesobot dive.

“I’ve always been interested in DNA and the environment,” Erin says. “When I was 12-years-old I wanted to study crime and become a forensic scientist — and in a way, I’m doing forensics now. I love this sweet spot where oceanography and molecular biology come together.”

Working alongside Lui Kawasumi, it takes Erin just under an hour to disassemble all the cartridges from Mesobot’s sampler, seal and label the filters, and stick them into a -80 degree freezer.

When Erin and I sailed together aboard the Sarmiento de Gamboa, she and other members of the hydro team collected water samples using a traditional CTD rosette and Niskin bottles. The method is tried and true, but it’s also very time consuming, and can include more possibilities for contamination of samples when they are filtered on the ship. The sampler on Mesobot, however, filters all the water at depth, which allows for a much more efficient and streamlined collection process.

Both Erin and Lui describe Mesobot’s unique ability to collect data from the Ocean Twilight Zone without disturbing the animals it encounters.

“It’s a stealthy way to see what is down there,” Lui says. “It’s like ninja biology!”

As on any oceanographic expedition, our operations are not all smooth sailing. While the weather off the coast of southern California is calm and stable, we run into issues with some of our systems. Mesobot’s camera doesn’t work correctly. The hybrid tether system for NUI fails during a deployment from the aft deck. I’m unsurprised (but still impressed) to see the ways in which the team take these challenges in stride, conducting professional assessments of what went wrong, and creating work-arounds to keep the mission going.

These ocean robots (and others like them) can do truly remarkable things — but they cannot do anything without the tenacity and determination of the humans who design, build, and operate them.

Dana Yoerger keeps a close eye on the monitors in the control van, displaying Mesobot’s progress through the Ocean Twilight Zone.